WoodMac wins: The consultancy giving cover to fossil fuel projects

Wood Mackenzie research was used to justify UK support for a gas megaproject in Mozambique and a new coal mine, in government and in court

The UK likes to present itself as a global climate leader. As host of the 2021 UN climate summit, it sent diplomats around the world to persuade other governments to curb emissions.

Back home, the government made two decisions that undermined its moral authority in the battle against climate change. It approved British taxpayer support for a huge gas project in Mozambique and gave planning permission for a new English coal mine.

Climate Home examined documents revealed by court proceedings and campaigners’ freedom of information requests and found a common denominator. In both decisions, politicians and civil servants relied on research from a company called Wood Mackenzie to justify their decisions.

Wood Mackenzie’s advice then persuaded judges that the UK government acted lawfully in supporting the Mozambique gas project.

The courts have yet to rule on the UK’s support for the new coal mine but Wood Mackenzie’s advice could again be pivotal – and contested. Climate and energy experts – including some working for the UK government – have criticised the consultancy’s research as “simplistic” and lacking credibility.

In its advice to UK Export Finance on the Mozambique project, Wood Mackenzie assumed the world was on course for a catastrophic 3C of global warming. The consultancy described a 2C limit, the minimum goal of the international Paris Agreement, as “highly ambitious” and unlikely to be met, therefore justifying more gas drilling.

It claimed the gas produced would reduce global emissions by displacing coal and oil, yet fudged the scale of pollution associated with customers burning the gas – known as scope 3 emissions.

The International Energy Agency has since found that no new fossil fuel projects are compatible with limiting global warming to 1.5C, a safer threshold.

Who are WoodMac?

Wood Mackenzie started out in 1923 as a stockbroking firm in the Scottish capital Edinburgh.

In the 1960s, fossil fuel companies struck oil off Scotland’s east coast the North Sea and the company, affectionately known as WoodMac, saw an opportunity. It started providing data, research and advice to the fossil fuel industry.

It now has offices in fossil fuel hubs across the world – from Texas, to Abu Dhabi, to Kazakhstan. Its website features customer testimonials from Chevron, Murphy Oil and Domo Chemicals.

New coal mine

Last month, the UK government sparked global fury by approving planning permission for a new coal mine in the north of England.

As the prime minister of Fiji, Frank Bainimarama pointed out, the UK fought hard to get anti-coal language into the text of the Glasgow agreement in 2021.

“Fossil fuels should be phased OUT – not up,” he tweeted.

The chair of the government’s official climate advisory body, Lord Deben said the decision “sends entirely the wrong signal to other countries about the UK’s climate priorities”.

Is this the future we fought for under the Glasgow Pact?

Fossil fuels should be phased OUT – not up. https://t.co/2BkBLxN6sV

— Frank Bainimarama (@JVBainimaramafj) December 8, 2022

Michael Gove, as minister for local government, was responsible for the decision. He based it on a 360-page report from town planner – and former coal miner – Stephen Normington.

In his report, Normington argued that Wood Mackenzie’s research was more useful than that of sources like the International Energy Agency (IEA) or the Climate Change Committee (CCC). The IEA is funded by its 31 member governments while the CCC is the UK government’s official climate change advisory body.

Campaigners arguing against the coal mine said no new mines for metal-making coal were needed. Wood Mackenzie projected that Europe would remain a large market for coking coal for several decades.

Friends of the Earth argued that Wood Mackenzie’s forecasts were not consistent with keeping global warming below 2C above pre-industrial levels, let alone 1.5C.

Normington found Wood Mackenzie’s analysis a “more realistic and currently foreseeable approach” as the UK’s climate targets were “incredibly challenging”.

Friends of the Earth are now challenging the decision in court. But Normington’s advice to Gove, which was informed by Wood Mackenzie’s research, is likely to count against campaigners in court.

Mozambique’s carbon bomb

Wood Mackenzie’s advice was similarly key in getting the UK government to financially support gas drilling plans by French oil major Total.

Total plans to extract gas from the seabed off the coast of northern Mozambique, bring it to shore, turn it into liquid and ship it around the world.

The project has been criticised by environmentalists, concerned about the emissions released from producing and burning the gas.

Friends of the Earth campaigners gather outside London’s Royal Courts of Justice in March 2022 (Pic: Friends of the Earth)

Local civil society and security analysts claim that the discovery of gas has worsened armed conflict in the region, by raising local peoples’ expectations for jobs and infrastructure and then failing to meet them, causing anger.

Anabela Lemos is the director of Friends of the Earth Mozambique. She told Climate Home that fishing communities had been relocated away from the sea. “All their way of life was completely destroyed,” she said.

She added that gas production could damage the plants and animals of the Qurimbas islands, a Unesco biosphere reserve. “Exploration on the sea is going to destroy everything,” she said.

The UK’s export credit agency, known as UK Export Finance (UKEF) offered to support the project with up to $1.15 billion. That’s $0.3bn in loans to British companies working on the project and $0.85bn worth of guarantees on loans from commercial banks. This would create an estimated 2,000 jobs for British workers.

Export credit agencies from the USA, Japan, Netherlands, South Africa, Italy and Thailand backed the project too, as did the African Development Bank.

How WoodMac got involved

When UKEF became interested in the project in 2019, it immediately ranked the project as “category A”, meaning it has the “potential to have adverse environmental and/or social impacts”.

In January 2020, the group of export credit agencies decided they needed to assess the greenhouse gas emissions of burning the gas which Total wanted to pump up. These are known as scope three emissions.

According to the high court judgment on the case, Total was involved in deciding who should make this assessment. The contract went to Wood Mackenzie.

They were already acting as “gas marketing consultants” for the project’s financial backers and had advised the African Development Bank on climate change considerations.

‘Somewhat simplistic’

Wood Mackenzie took about a month to produce a 23-page draft report. A disclaimer in the last slide of the report says “we do not guarantee fairness, completeness or accuracy”.

Privately, UKEF officials were scathing about the firm’s efforts. In emails revealed in court, one UKEF employee described it as “very light”. Another said it operated on a “somewhat simplistic level”.

A fisherman in Milamba before Total’s project (Friends of the Earth Mozambique)

Specifically, Wood Mackenzie refused to do what they were initially asked to do – calculate the emissions from burning the project’s gas.

They said it wasn’t possible to know where the gas would end up and what it would be used for – so the scope of their work was limited by agreement with UKEF.

Ben Caldecott is an expert in sustainable finance and member of the Export Guarantees Advisory Council, which advises UKEF. In May 2020, he told UKEF that Wood Mackenzie’s failure to calculate emissions was “a big gap in the analysis”.

Julian Critchlow was the head of energy transformation at the UK’s energy ministry. He said the failure “undermined the credibility of the assessment”.

Estimates are possible

There is a method to calculate scope three emissions known as the greenhouse gas protocol.

This was developed by the World Resources Institute and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development.

Most of the companies which report their scope three emissions use this method and Total’s expert described it in court as “well known and established”.

The UK parliament’s environmental audit committee had recommended that UKEF use this method.

World Bank adaptation funds slept through Pakistan’s record flooding

UKEF told Climate Home that “the [greenhouse gas] protocol recognises the significant challenges in accounting for Scope 3 emissions which is an optional reporting category” and they had used “expert external consultants”.

A spokesperson for Wood Mackenzie said that their contract prevents them from discussing why they didn’t use the greenhouse gas protocol method.

The UK’s energy ministry eventually came up with a figure for scope three emissions – but only after prime minister Boris Johnson had approved support for the project.

Officials estimated that producing the gas over the project’s lifteimee would emit 322 million tonnes of carbon dioxide and burning it would emit a further 806Mt. Together, this is roughly equivalent to a year’s worth of emissions from Japan.

‘Transition fuel’

While claiming not to be able to calculate the emissions of burning the gas, Wood Mackenzie did feel able to conclude that Mozambique’s gas would displace more polluting fossil fuels like coal and would therefore help in the fight in climate change.

This controversial conclusion was highlighted on the first page of their report which said simply: “Gas and LNG are fundamental to the energy transition.”

The report later claims “oil and, in particular gas, are fundamental to enabling the energy transition without massive disruption”.

Wood Mackenzie predicted that Mozambique’s gas will be good for the climate because “there appears to be particular scope for [the gas] to displace coal in power generation in China, India and Indonesia”.

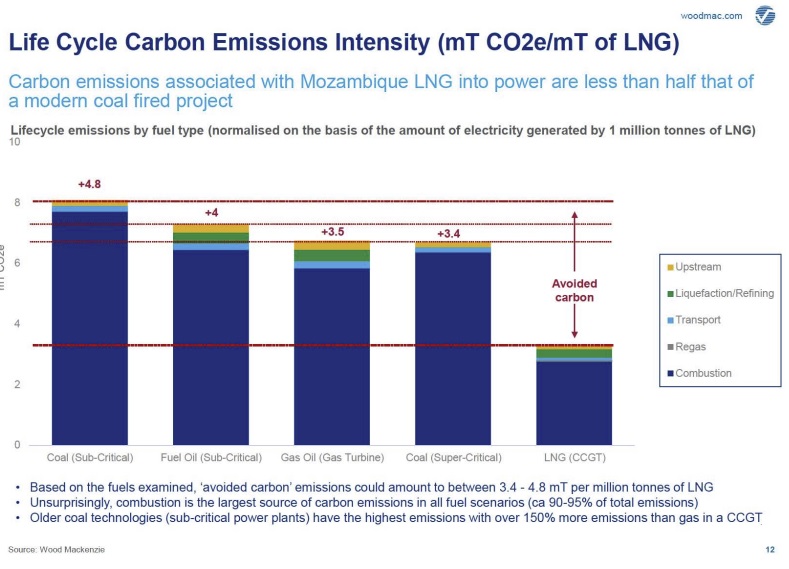

Of the 15 slides, three are on how gas is less carbon-intensive than coal or oil. None of these slides compare gas to zero-carbon energy sources like renewables or nuclear.

Wood Mackenzie’s report compared gas to coal and oil but not renewables or nuclear

This is still broadly Wood Mackenzie’s view. A spokesperson told Climate Home that gas would displace coal, particularly in Asia. Paired with carbon capture, gas will provide flexible electricity and hydrogen, they added.

Even in 2019, this clashed with advice from the IEA. In 2019, the organisation warned that while “gas can bring environmental benefits,” that “new gas infrastructure can lock in… emissions for the future”.

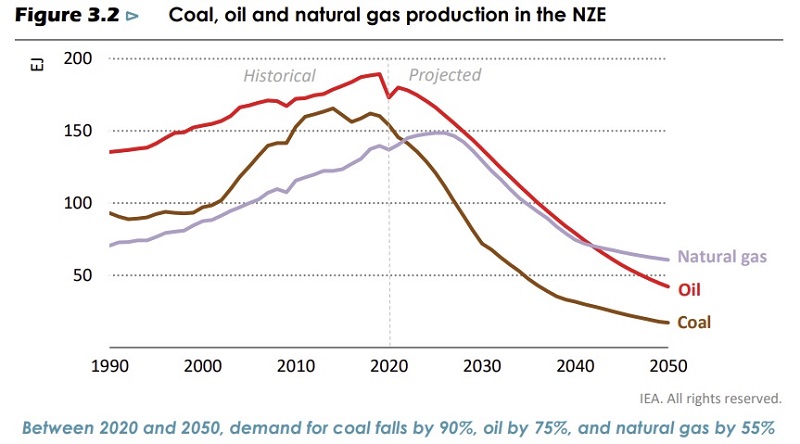

The IEA’s position has since hardened. It found in 2021 that no new gas projects are compatible with 1.5C of global warming and “net zero means huge declines in the use of coal, oil and gas”.

In 2021, the IEA said that gas production must fall drastically if the world is limit global warming to 1.5C (Pic: IEA)

1.5 not modelled

At the time of its report, Wood Mackenzie assumed that global warming would reach 3C. It described its scenario limiting global warming to 2.5C as an “accelerated energy transition”.

The report also references the International Energy Agency’s 2019 sustainable development scenario, which models how the world can limit global warming to 2C.

Wood Mackenzie describe this 2C scenario as “highly ambitious”. In its conclusions, it claims that limiting global warming to 2C will be “challenging, meaning that there is likely upside for [liquified natural gas]”.

Wood Mackenzie did not refer at all to the 1.5C target, which all governments agreed to “pursu[e] efforts” towards in 2015’s Paris Agreement.

Mexico plans to ban solar geoengineering after rogue experiment

This framing of temperature targets clashes with UK prime minister Boris Johnson’s speech at Cop26 in Glasgow at the end of 2021.

He told the summit that 2C “jeopardise[s] the food supply for hundreds of millions of people as crops wither, locusts swarm”.

Uppping that target to three degrees “add[s] more wildfires and cyclones – twice as many of them, five times as many droughts and 36 times as many heatwaves”.

The world is currently at 1.2C of global warming and is already suffering more and worse climate disasters.

Asked if it still regards 2C as “highly ambitious”, a Wood Mackenzie spokesperson said it “continues to be challenging but this challenge can be overcome”.

The company produced its first 1.5C scenario in February 2021. It claims that demand for gas can “be resilient” under this scenario if carbon capture and storage technology takes off.

Lightweight but influential

While it was scorned by experts, the Wood Mackenzie report played a key role in persuading UKEF and the UK government to back the project.

Later, the report proved critical in British judges’ decision that the UK government acted lawfully in approving the support – as they had received expert advice encouraging them to do so.

A key UKEF committee signed off on the support at a meeting on April 30 2020.

The meeting’s minutes refer to Wood Mackenzie’s support and echo its findings that the gas would help some Asian countries “transition to a lower carbon economy”.

This committee then advised the UKEF’s then head, an ex-banker called Louis Taylor.

On 1 June, Taylor asked then international trade secretary Liz Truss to support the project.

He advised her to read UKEF’s climate change report on the project, which was largely based on Wood Mackenzie’s report.

Ten days later, Truss signed off on it. Two days later, then finance minister now prime minister Rishi Sunak did the same.

Now UK prime minister Rishi Sunak holds up a symbolically green briefcase at Cop26 (Photo credit: Treasury)

But the foreign minister Dominic Raab, international development minister Anne-Marie Trevelyan and the business and energy minister Alok Sharma opposed the project on climate grounds.

Sharma, who was also Cop26 president-elect, said in an email that “it does not seem credible to support this proposal” given the UK’s hosting of the summit and it’s new policy of not funding coal projects abroad.

Down to Johnson

With ministers divided, Taylor went to prime minister Boris Johnson for a verdict.

Boris Johnson at Cop26, six months after he approved support for Total’s gas project (UNFCCC/Kiara Worth)

By that stage of his leadership, the government’s scientists and his environmentalist girlfriend had converted Johnson from a climate sceptic to an avowed environmentalist. So his support for the gas deal was not certain.

Taylor told Johnson what Wood Mackenzie had told his advisors. He claimed gas “is generally recognised as a transition fuel” and that it was not possible to accurately assess the emissions from burning the gas.

Six days later, Johnson signed off on the project. He asked only that the government look into how a carbon capture and storage facility could be created to offset the project’s emissions.

Six months later, Johnson told a climate summit that the UK would end support for fossil fuels.

At Cop26, two more of the project’s backers – the US and Italy – did the same. A few months later, Japan joined them.

But the Mozambique gas project snuck in under the line. It has not been affected by the new bans.

Legal cover

UK taxpayer support was still not guaranteed. In December 2021, campaigners from Friends of the Earth took the UK government to court, arguing that the decision was not compatible with the Paris agreement.

They first made their case to two British high court judges who came to different conclusions.

Justice Justine Thornton found “the failure to quantify Scope 3 emissions, as well as other flaws in the climate assessment, mean that there is no rational basis on which to demonstrate that the funding for the Project is consistent with Article 2(1)(c) of the Paris Agreement”.

This article says governments must make “finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development”.

But judge Jeremy Stuart-Smith disagreed. So the case was kicked up to a higher court.

There, two appeals judges put a lot of weight on Wood Mackenzie’s assessment.

Their ruling says there was “uncertainty” about whether the project would reduce or increase emissions and “the reports and materials obtained by the respondents made clear that the precise outcome could not be predicted”. Therefore they considered the government’s decision that the project was compatible with the Paris agreement was “tenable”.

As British judges are unelected, they are wary of overturning decisions made by elected politicians unless they clearly break the law.

What happens next?

Friends of the Earth lawyers are mulling over whether to take the case to the supreme court. If the UK does back the project, it is likely to be the last foreign fossil fuel project it supports.

Lemos is still hopeful. She said: “We believe there is a chance for an appeal and there’s a chance for us to win… I still have hope that things can turn”.

On the ground in Mozambique, the project has been suspended because of a vicious armed insurgency, which has forced about a million people to flee.

In October 2022, Total said it was preparing to restart the project in early 2023. It made similar announcements in 2022.

Case for the defence

A spokesperson for Wood Mackenzie said that the company had delivered what the client had asked for and the client had accepted its work.

The spokesperson said the company “did include analysis of scope three emissions with clear guidance about potential constraints to the analysis”.

A spokesperson for Total said that the project’s operational emissions are lower than other similar projects, Total supports keeping temperatures well below 2C above pre-industrial levels. They claimed that gas is a “transition fuel” which will displace coal and help Total meet its target to reach net zero by 2050.

The spokesperson added that Total “strongly refutes” claims that the discovery of gas has worsened armed conflict. They pointed to the creation of an economic development information office in the city of Pemba and a promise to train more than 2,500 young people.

A spokesperson for UK Export Finance told Climate Home they welcomed the court’s latest decision and “remain confident that UKEF follows robust and internationally recognised due diligence before providing any support for overseas projects”.

They said the UK government no longer supports fossil fuels overseas except in limited circumstances and is “committed to helping countries across the globe move away from their dependence on fossil fuels and accelerate to net zero”. UKEF has pledged to support more green exports and decarbonise its portfolio by 2050.

Comments are closed.